Lena Dunham is an incredibly interesting young woman. The creator of HBO series Girls, I greatly admire Dunham's creativity as a writer and director in crafting a show for and about twenty-something feminist women struggling with life in New York.

She recently published her first memoir - Not that Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She Has 'Learned' (2014) - which contains Dunham's reminiscences loosely grouped in sections titled Love & Sex, Body, Friendship, Work, and Big Picture. In a series of essays Dunham explores various vignettes from her life, separated by snappy lists ('15 things I learned from my mother'), in a non-linear, disorderly manner. The book has attracted a fair amount of controversy for some of its contents, and for the multi-million dollar advance given to the author.

Readers wanting to know how a young woman achieved such success as a filmmaker will not find it here. In fact, those seeking to emulate her creative journey will be none the wiser. I was hoping to learn what inspired her and how she has managed her success. Instead I learned too much about Dunham's narcissism and neuroses.

Dunham writes that she lives "in a world that is almost compulsively free of secrets." She puts herself out there - emotionally, physically, artistically - and there is a lot to admire about that. But at the same time I kept wishing that she was more self-protective. Do we need to hear about every sex act she has performed? Does she realise how privileged she sounds? Is she making up these stories anyway?

There is humour here and there (not dissimilar to Girls in that respect) and there are moments of depth and insight. But largely I felt disappointed by Not That Kind Of Girl because it was Not That Kind of Memoir. Perhaps that was my problem - hoping it would be something it wasn't.

Sunday, 18 January 2015

Tuesday, 13 January 2015

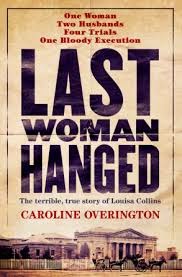

Arsenic and Old Lace

Last Woman Hanged (2014) by Caroline Overington tells the true tale of Louisa Collins, convicted murderer who was executed in Sydney in 1889. Found guilty of poisoning her second husband Michael Collins with arsenic, Louisa was hanged, leaving her young children in the care of the State.

Louisa was born in Belltrees near Scone, NSW and was married at nineteen to local butcher Charles Andrews. She spent much of the next twenty years pregnant with the nine children she would bear. Possibly ill-matched, Andrews was a committed family man who adored his wife, while Louisa perhaps missed out on many experiences that she would have enjoyed in lieu of domesticity.

When the couple moved to Botany in 1886 so that Andrews could work as a wool-washer, they took in boarders to make ends meet. Rumours circulated in the tight Botany community that Louisa enjoyed drinking with the men who stayed in their home.

In early 1887 Andrews took ill and after a few days of excruciating pain he died. Louisa's behaviour immediately after his death was viewed unfavourably by police and local gossips, especially as she did not don mourning clothes and applied for access to Andrews life insurance. Within two months of being widowed, Louisa married Michael Collins, a former boarder, pregnant with his child.

Collins was not good with money and the insurance funds dissipated quickly. Their infant son John died, and Louisa's older children were not fond of their new stepfather. In mid-1888 Collins took ill, with symptoms similar to Andrews, and died on 8 July. Almost immediately Louisa was arrested for his murder by poisoning.

What happened next was appalling. Louisa Collins was tried - four times - by a prosecution determined to convict. The evidence against her was entirely circumstantial and there was much to suggest that both men may have became poisoned through their work as wool washers as skins were treated with arsenic. She had an extremely ineffective defence attorney and her young daughter May was compelled to give evidence against her. The first three trials resulted a hung jury, but the last, with a backdrop of media frenzy, voted to convict. These four trials occurred in rapid succession with gross misconduct on the part of many of the judges.

What happened next was appalling. Louisa Collins was tried - four times - by a prosecution determined to convict. The evidence against her was entirely circumstantial and there was much to suggest that both men may have became poisoned through their work as wool washers as skins were treated with arsenic. She had an extremely ineffective defence attorney and her young daughter May was compelled to give evidence against her. The first three trials resulted a hung jury, but the last, with a backdrop of media frenzy, voted to convict. These four trials occurred in rapid succession with gross misconduct on the part of many of the judges.

Overington combs through the evidence for and against Louisa and highlights many inconsistencies which lead the first three juries to be unconvinced of her guilt beyond reasonable doubt. She also explored the historical context of the rise of the women's suffrage campaign, the temperance movement and the sensationalism of the media. What emerges is a travesty of justice in which a woman was killed by the State in a most horrific way.

This book was intriguing in many respects with Overington's skills as a journalist lending weight to her research. I particularly enjoyed the story of the early feminism in Australia. I learned a great deal about how autopsies were performed in hotels, the travel by tram around Sydney, and about the medical fraternity of the time. Although I need no further evidence to support my stance against capital punishment, this book was a reminder of how State-sanctioned killing is immoral and unjust.

I did not particularly like Overington's writing style, however, and felt that some of her turns of phrase distanced me from the content. She included many asides where she presented information with a modern gaze, and would have been better off sticking purely to the facts. An example is when she was talking about Alexander Green, one of the first hangmen in NSW. Overington writes "like most normal people, Green did not set out to become a hangman...". This sentence jarred me as judgemental and unnecessary. Later she writes about Louisa's fate moving to Parliament house "... in about the time it took to traverse the distance by foot. Well, not quite, but the point is made." The point could have been made without the poor analogy. This occurred regularly throughout the book and I wished it had been better edited prior to publication to remove some of these clunky asides.

But overall I am pleased that I read the book and had a glimpse of this time in our history. This book is recommended to those with an interest in history or the judicial system.

Louisa was born in Belltrees near Scone, NSW and was married at nineteen to local butcher Charles Andrews. She spent much of the next twenty years pregnant with the nine children she would bear. Possibly ill-matched, Andrews was a committed family man who adored his wife, while Louisa perhaps missed out on many experiences that she would have enjoyed in lieu of domesticity.

When the couple moved to Botany in 1886 so that Andrews could work as a wool-washer, they took in boarders to make ends meet. Rumours circulated in the tight Botany community that Louisa enjoyed drinking with the men who stayed in their home.

In early 1887 Andrews took ill and after a few days of excruciating pain he died. Louisa's behaviour immediately after his death was viewed unfavourably by police and local gossips, especially as she did not don mourning clothes and applied for access to Andrews life insurance. Within two months of being widowed, Louisa married Michael Collins, a former boarder, pregnant with his child.

Collins was not good with money and the insurance funds dissipated quickly. Their infant son John died, and Louisa's older children were not fond of their new stepfather. In mid-1888 Collins took ill, with symptoms similar to Andrews, and died on 8 July. Almost immediately Louisa was arrested for his murder by poisoning.

What happened next was appalling. Louisa Collins was tried - four times - by a prosecution determined to convict. The evidence against her was entirely circumstantial and there was much to suggest that both men may have became poisoned through their work as wool washers as skins were treated with arsenic. She had an extremely ineffective defence attorney and her young daughter May was compelled to give evidence against her. The first three trials resulted a hung jury, but the last, with a backdrop of media frenzy, voted to convict. These four trials occurred in rapid succession with gross misconduct on the part of many of the judges.

What happened next was appalling. Louisa Collins was tried - four times - by a prosecution determined to convict. The evidence against her was entirely circumstantial and there was much to suggest that both men may have became poisoned through their work as wool washers as skins were treated with arsenic. She had an extremely ineffective defence attorney and her young daughter May was compelled to give evidence against her. The first three trials resulted a hung jury, but the last, with a backdrop of media frenzy, voted to convict. These four trials occurred in rapid succession with gross misconduct on the part of many of the judges.Overington combs through the evidence for and against Louisa and highlights many inconsistencies which lead the first three juries to be unconvinced of her guilt beyond reasonable doubt. She also explored the historical context of the rise of the women's suffrage campaign, the temperance movement and the sensationalism of the media. What emerges is a travesty of justice in which a woman was killed by the State in a most horrific way.

This book was intriguing in many respects with Overington's skills as a journalist lending weight to her research. I particularly enjoyed the story of the early feminism in Australia. I learned a great deal about how autopsies were performed in hotels, the travel by tram around Sydney, and about the medical fraternity of the time. Although I need no further evidence to support my stance against capital punishment, this book was a reminder of how State-sanctioned killing is immoral and unjust.

I did not particularly like Overington's writing style, however, and felt that some of her turns of phrase distanced me from the content. She included many asides where she presented information with a modern gaze, and would have been better off sticking purely to the facts. An example is when she was talking about Alexander Green, one of the first hangmen in NSW. Overington writes "like most normal people, Green did not set out to become a hangman...". This sentence jarred me as judgemental and unnecessary. Later she writes about Louisa's fate moving to Parliament house "... in about the time it took to traverse the distance by foot. Well, not quite, but the point is made." The point could have been made without the poor analogy. This occurred regularly throughout the book and I wished it had been better edited prior to publication to remove some of these clunky asides.

But overall I am pleased that I read the book and had a glimpse of this time in our history. This book is recommended to those with an interest in history or the judicial system.

Sunday, 4 January 2015

Larger than Life

The latest Quarterly Essay (QE56) by Guy Rundle is Clivosaurus: The Politics of Clive Palmer (November 2014). An intriguing tale of a politician and a flawed political system, Rundle has written a witty, pithy account of Palmer's political rise and what he may mean for Australia and our political system.

In 2013 Clive Palmer - Queenslander, self-proclaimed billionaire, mining magnate, dinosaur enthusiast and Titanic-fan - formed his own political party and sought appointment as the member for Fairfax in the federal election. The Palmer United Party (PUP) was initially dismissed by the media and the mainstream parties as a sideshow without any chance of winning, but surprised many by securing one seat in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate. Canberra hasn't been the same since...

A larger-than-life figure, Palmer has always seemed to me to be a bit of an eccentric, bumbling clown - thumbs-upping in photo shoots, making up policy as he goes along and generating publicity stunts. Whether it is through his twerking on TV, storming out of interviews, or his policy flip-flops, I could never seem to get a handle on who Clive Palmer is, and what he hopes to achieve. I cynically presumed he took to politics to further his own ego and to serve his own ends (like reducing taxes on mining companies). In this essay, Rundle attempts to get to the heart of the mystery - who is Clive Palmer?

Along the way we learn about Palmer's upbringing, his business ventures and his poetry (Rundle drew heavily from Sean Parnell's Clive - The Story of Clive Palmer (2013) to flesh out Palmer's backstory). This was extremely interesting and presented Palmer as a much more complex character than I had given him credit for. While Palmer's philosophy and politics do not align with mine, and I am still very sceptical about his motives, I can no longer write him off as merely a media-hungry buffoon.

Along the way we learn about Palmer's upbringing, his business ventures and his poetry (Rundle drew heavily from Sean Parnell's Clive - The Story of Clive Palmer (2013) to flesh out Palmer's backstory). This was extremely interesting and presented Palmer as a much more complex character than I had given him credit for. While Palmer's philosophy and politics do not align with mine, and I am still very sceptical about his motives, I can no longer write him off as merely a media-hungry buffoon.

Rundle's essay also exposes the flaws of the Australian political system - which is marred by loop-holes and complexities. The number of fringe candidates, satirical parties, and outright odd-balls that make it on to the ballot (and worse still into Parliament) is evidence of a system that needs review. The system can be gamed, with 'preference-whisperers' and backroom deals, resulting in the election of people with very low primary votes. But this is not new, rather it is a known problem that no one seems willing to tackle.

Illuminating the 'triple lock' of the Australian system - compulsory voting, preferential voting and taxpayer campaign funding - Rundle shines a light on areas that need to be urgently addressed. He calls for an open discussion about creating a more democratic system and lists items for inclusion in this debate (voluntary voting, multi-member electorates, optional preferences, campaign spending, role of the governor general). I whole heartedly agree.

Clivosaurus was another excellent essay in this series. My reviews of past Quarterly Essays are also on this blog:

In 2013 Clive Palmer - Queenslander, self-proclaimed billionaire, mining magnate, dinosaur enthusiast and Titanic-fan - formed his own political party and sought appointment as the member for Fairfax in the federal election. The Palmer United Party (PUP) was initially dismissed by the media and the mainstream parties as a sideshow without any chance of winning, but surprised many by securing one seat in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate. Canberra hasn't been the same since...

A larger-than-life figure, Palmer has always seemed to me to be a bit of an eccentric, bumbling clown - thumbs-upping in photo shoots, making up policy as he goes along and generating publicity stunts. Whether it is through his twerking on TV, storming out of interviews, or his policy flip-flops, I could never seem to get a handle on who Clive Palmer is, and what he hopes to achieve. I cynically presumed he took to politics to further his own ego and to serve his own ends (like reducing taxes on mining companies). In this essay, Rundle attempts to get to the heart of the mystery - who is Clive Palmer?

Along the way we learn about Palmer's upbringing, his business ventures and his poetry (Rundle drew heavily from Sean Parnell's Clive - The Story of Clive Palmer (2013) to flesh out Palmer's backstory). This was extremely interesting and presented Palmer as a much more complex character than I had given him credit for. While Palmer's philosophy and politics do not align with mine, and I am still very sceptical about his motives, I can no longer write him off as merely a media-hungry buffoon.

Along the way we learn about Palmer's upbringing, his business ventures and his poetry (Rundle drew heavily from Sean Parnell's Clive - The Story of Clive Palmer (2013) to flesh out Palmer's backstory). This was extremely interesting and presented Palmer as a much more complex character than I had given him credit for. While Palmer's philosophy and politics do not align with mine, and I am still very sceptical about his motives, I can no longer write him off as merely a media-hungry buffoon.Rundle's essay also exposes the flaws of the Australian political system - which is marred by loop-holes and complexities. The number of fringe candidates, satirical parties, and outright odd-balls that make it on to the ballot (and worse still into Parliament) is evidence of a system that needs review. The system can be gamed, with 'preference-whisperers' and backroom deals, resulting in the election of people with very low primary votes. But this is not new, rather it is a known problem that no one seems willing to tackle.

Illuminating the 'triple lock' of the Australian system - compulsory voting, preferential voting and taxpayer campaign funding - Rundle shines a light on areas that need to be urgently addressed. He calls for an open discussion about creating a more democratic system and lists items for inclusion in this debate (voluntary voting, multi-member electorates, optional preferences, campaign spending, role of the governor general). I whole heartedly agree.

Clivosaurus was another excellent essay in this series. My reviews of past Quarterly Essays are also on this blog:

- Unfinished Business: Sex, Freedom and Misogyny (QE50) by Anna Goldsworthy

- The Prince: Faith Abuse and George Pell (QE51) by David Marr

- Lost In Translation: In Praise of a Plural World (QE52) by Linda Jaivin

- That Sinking Feeling: Asylum Seekers and the Search for the Indonesian Solution (QE53) by Paul Toohey

Thursday, 1 January 2015

Planning for 2015

It is never wise to plan my reading for the year. As soon as I decide what I am going to read, I get distracted by new novels and non-fiction that is published throughout the year and by books I find lurking on my shelves waiting for their time to be read.

But I do have a overall plans to try and read at least two books a month (so 24 for the year). I would like to try and vary my reading some more and tackle some of the books I have recently been given.

Biographies are always enjoyable. I like hearing of how other people have lived and the challenges they have overcome. The biographies I have on my to-be-read pile include:

The Paying Guests (2014) by Sarah Waters

All the Birds, Singing (2013) by Evie Wyld

Nora Webster (2014) by Colm Toibin

Top Secret Twenty-One (2014) by Janet Evanovich

A Feast for Crows (2005) by George R R Martin - fourth instalment of Song of Ice and Fire series.

World of Wonders (1975) by Robertson Davies - final instalment of the Deptford Trilogy which is a long overdue read.

But I do have a overall plans to try and read at least two books a month (so 24 for the year). I would like to try and vary my reading some more and tackle some of the books I have recently been given.

- My Story (2014) by Julia Gillard (Update: read April 2015)

- Not That Kind of Girl (2014) by Lena Dunham (Update: read January 2015)

- Yes Please (2014) by Amy Poehler (Update: read February 2015)

- Hard Choices (2014) by Hillary Rodham Clinton

I guess that list says something about my admiration of strong, brave, funny, feminist women. However, I may throw in a volume by Stephen Fry along the way.

In addition to biographies, my keen interest (as always) is political economy - with special attention to social policy, wealth inequality, and gender issues. On my list for 2015 are:

- A Bigger Prize (2014) by Margaret Heffernan

- Slavery Inc - The Untold Story of International Child Sex Trafficking (2010) by Lydia Cacho

- The Omnivore's Dilemma (2006) by Michael Pollan (Update: read February 2015)

- Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013) by Thomas Piketty

- Quarterly Essay 56 - Clivosaurus (2014) by Guy Rundle (Update: read January 2015)

- Quarterly Essay 55 - A Rightful Place (2014) by Noel Pearson

- Quarterly Essay 54 - Dragon's Tail: The Lucky Country After the China Boom (2014) by Andrew Charlton

I will have another year's worth of Quarterly Essay arriving and other non-fiction to add to this list as I go along.

In terms of fiction, my to-be-read pile changes regularly as I am often taken by a theme or an author or dip back in to re-read an old favourite (such as my annual Harry Potter spree!). On the list are:

Add to this list some of the new books expected from Kazuo Ishiguro (The Buried Giant), Anne Tyler (A Spool of Blue Thread), Irvine Welsh (A Decent Ride), and hopefully a new Robert Galbraith.

So overall it looks like a great year for reading. Can't wait!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)