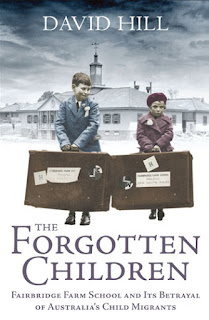

From 1938 to 1973 thousands of poor British children emigrated to Australia, Canada and Rhodesia under the Fairbridge Schools scheme. Founder Kingsley Fairbridge was concerned about the rising number of poor families in Britain and the need for white settlement in British colonies. His solution was to create a child migration scheme wherein poor children would be sent to farm schools in distant lands and trained to become farmers and farmer's wives. Parents, convinced they would be providing their children with opportunities for a better life, signed away their rights and, in many instances, never saw their children again.

Author David Hill was one of the more than 7000 children to be sent to Australia as a child migrant. He emigrated in 1959 as part of the One Parent program, in which single parents would send their children in advance to Australia, to be reunited once the parent had travelled to Australia, secured employment and was ready to take their children back. Hill and his two brothers came in their early teens and found themselves at the Fairbridge Farm School in Molong NSW. He documents his story, and that of many others, in The Forgotten Children (2007).Saturday, 19 June 2021

The Survivors

Friday, 18 June 2021

Miles Franklin Shortlist 2021

The 2021 Miles Franklin Award shortlist was announced this week. When I predicted which titles would make the cut, I had expected Sofie Laguna, Laura Jean McKay, Miranda Riwoe, and Nardi Simpson to make the shortlist. Surprisingly none of these authors were included.

The shortlist is made up of the following works:- Aravind Adiga - Amnesty

- Robbie Arnott - The Rain Heron

- Daniel Davis Wood - At the Edge of the Solid World

- Amanda Lohrey - The Labyrinth

- Andrew Pippos - Lucky's

- Madeline Watts - The Inland Sea

“In various ways each of this year’s shortlisted books investigate destructive loss: of loved ones, freedom, self and the environment. There is, of course, beauty and joy to be found, and decency and hope, largely through the embrace of community but, as the shortlist reminds us, often community is no match for more powerful forces."

The Winner of the $60,000 prize will be revealed on 15 July 2021.

Sunday, 6 June 2021

Self Portrait

There has been a lot of hype surrounding Raven Leilani's debut novel Luster (2020). Winner of the Kirkus Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction, Luster was longlisted for the 2021 Women's Prize and the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. It also appeared on countless 'best books of 2020' lists.

The narrator is Edie, a twenty-three year old black artist working in an all-white office in a New York City publishing firm. She is ungrounded, having lost both her parents, living in a roach-infested apartment, and engaging in a string of meaningless encounters with coworkers. Online she meets Eric, a forty-something white guy from New Jersey in a seemingly open marriage. They begin a relationship, following strict rules crafted by Eric's wife Rebecca.When Edie loses her job and her apartment, she does some gig work as a delivery rider and by chance happens to meet Rebecca, who invites Edie to come and live in the couple's guest room. Over time, Edie develops a connection with Akila, the couple's adopted twelve year old black daughter. Both of them are outsiders in this strange suburban landscape.

There is something about Leilani's writing that attracts readers. The author is sharp, observant and there is an urgency with which she propels this story along. Through Edie, Leilani has a lot to say about race, class, sex, poverty and privilege. There is a playfulness in the pop culture references, the voyeurism and the observations Edie makes of the world around her.

Generally, I like unlikable characters and unreliable narrators. But everyone in this book was unlikable and unreliable. Other than Edie, there is not much character development and as such I found it hard to care about anyone in the novel. Despite not loving this book, I did enjoy Leilani's writing and I look forward to seeing what she comes up with next.