From 1938 to 1973 thousands of poor British children emigrated to Australia, Canada and Rhodesia under the Fairbridge Schools scheme. Founder Kingsley Fairbridge was concerned about the rising number of poor families in Britain and the need for white settlement in British colonies. His solution was to create a child migration scheme wherein poor children would be sent to farm schools in distant lands and trained to become farmers and farmer's wives. Parents, convinced they would be providing their children with opportunities for a better life, signed away their rights and, in many instances, never saw their children again.

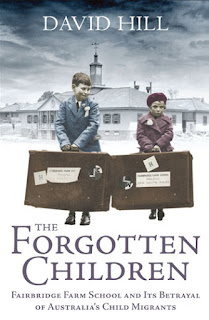

Author David Hill was one of the more than 7000 children to be sent to Australia as a child migrant. He emigrated in 1959 as part of the One Parent program, in which single parents would send their children in advance to Australia, to be reunited once the parent had travelled to Australia, secured employment and was ready to take their children back. Hill and his two brothers came in their early teens and found themselves at the Fairbridge Farm School in Molong NSW. He documents his story, and that of many others, in The Forgotten Children (2007).This book is a heartbreaking read. Part memoir and part historical study, Hill has researched extensively and spoken with countless Fairbridge children who recount in similar detail their experiences - including the physical, sexual and psychological abuse they suffered - at the Molong school. It was devastating to read how siblings were separated upon arrival, denying young children the opportunity to be with someone who cared for them. They were also denied adequate food, clothing, and a meaningful education. Further, while purporting to train children to become farmers, Fairbridge failed on that measure too, with children becoming adults with limited skills to find success in a career in or in relationships.

Hill describes the origins of the Fairbridge scheme, the journey to Australia and arrival at Molong, a day in the life of the children, their work and education, and how they left Fairbridge. Readers can quickly understand what it must have been like for these young children. It was wonderful to read the accounts of so many former child migrants, expressing in their own words what it was like for them. Unfortunately, there was a significant repetition, not in the personal stories but in Hill's narrative, which was distracting as a reader.

Over the past few years I have learned a great deal about the institutionalisation of children and the intergenerational trauma that stems from it. I have spent many hours reading the report from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse and the 2001 Senate Report Lost innocents: Righting the Record - Report on Child Migration. What I have learned from these reports and from The Forgotten Children is that there were so many opportunities to stop the neglect and abuse, but the children were repeatedly failed by individuals, organisations and governments. Hill gained access to many 'secret' reports in which child welfare agents sounded the alarm about what was happening at Fairbridge, only to have these reports buried or discounted. While it is small consolation, the NSW Government has agreed to be a funder of last resort for the Fairbridge Society Molong under the National Redress Scheme, so at least there is an opportunity for some of the children to have their suffering acknowledged.

On 16 November 2009, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a formal apology to the 'Forgotten Australians', in a moving speech which acknowledged the 'ugly chapter in our nation's history'. While it is undoubtedly an ugly chapter, it is essential that we know about what happened at places like Fairbridge so that we learn from our past. Thank you David Hill for sharing your story and that of other care leavers. You have shined a light into this dark corner of our history.