In 1959 on a farm in Holcolm, Kansas, the Clutter family was brutally murdered. The death of the farmer, his wife and two of their children, shocked the local residents who were horrified at the violence and perplexed by the motive for the killings.

When news of the crime reached New York, author Truman Capote - a successful novelist, celebrity darling and bon-vivant - sensed there was more to the story. He travelled with his childhood friend, To Kill a Mockingbird author Harper Lee, to Kansas to investigate. Over the next few years Capote became engrossed in the mystery. He became close to the men arrested for the crime and to the sheriff determined to see justice done. In 1966 Capote published In Cold Blood, his story of the crime, and in doing so invented a new form of writing - a merging of journalism and fiction that Capote called the 'nonfiction novel'.

I have read In Cold Blood twice and each time I marvel at the way the Capote has crafted this book. Describing in minute detail the events on the day of the murder, the trial and the aftermath, Capote draws the reader in to the scene of the crime. He alternates the narrative with the life stories of Perry Smith and Dick Hickock - the men who would convicted of the murders - and the tale of Alvin Dewey, the local policeman who would not rest until they were convicted.

Capote apparently took no notes as he interviewed people for his research and relied on memory to recreate the dialogue he recalls in the book. So perhaps it is here that a degree of creative license enabled him to shape the tale to fit his vision of a good story. The result is a tightly woven crime thriller, built on unfolding layers which, in the end, also presents the moral dilemma of capital punishment. For me, In Cold Blood is as close to perfect as a novel can get - a page turner with a fascinating story, interesting characters and beautifully descriptive prose.

It is no wonder that the story garnered the attention of Hollywood. In recent years two films have been made focussing on Capote's time researching and writing about the crime.

The film Capote (2005) stars Philip Seymour Hoffman in an Academy Award winning performance as the author. Harper Lee is portrayed by Catherine Keener. Chris Cooper plays Alvin Dewey. The film was also nominated for best picture, supporting actress, director and adapted screenplay. The film is excellent and clearly demonstrates how Truman was affected by the murders and his involvement in writing this book.

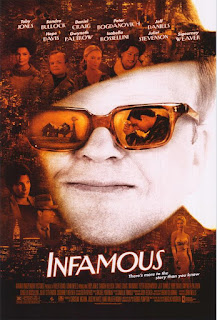

The film Capote (2005) stars Philip Seymour Hoffman in an Academy Award winning performance as the author. Harper Lee is portrayed by Catherine Keener. Chris Cooper plays Alvin Dewey. The film was also nominated for best picture, supporting actress, director and adapted screenplay. The film is excellent and clearly demonstrates how Truman was affected by the murders and his involvement in writing this book.  The following year, Infamous (2006) was released. In this film English actor Toby Jones plays Capote. He is joined by Sandra Bullock as Harper Lee and Daniel Craig as murderer Perry Smith. The film also features a who's-who of Hollywood with cameos by Jeff Daniels, Peter Bogdanovich, Gwyneth Paltrow, Sigourney Weaver, Isabella Rosellini, Hope David and Juliet Stevenson.

The following year, Infamous (2006) was released. In this film English actor Toby Jones plays Capote. He is joined by Sandra Bullock as Harper Lee and Daniel Craig as murderer Perry Smith. The film also features a who's-who of Hollywood with cameos by Jeff Daniels, Peter Bogdanovich, Gwyneth Paltrow, Sigourney Weaver, Isabella Rosellini, Hope David and Juliet Stevenson. Both films are excellent and it is hard to compare and contrast. Hoffman and Jones give different, equally excellent, portrayals of Capote. There is a lot to admire in both films, and they are well worth seeing, but on balance I think Capote is the better film.