Louisa was born in Belltrees near Scone, NSW and was married at nineteen to local butcher Charles Andrews. She spent much of the next twenty years pregnant with the nine children she would bear. Possibly ill-matched, Andrews was a committed family man who adored his wife, while Louisa perhaps missed out on many experiences that she would have enjoyed in lieu of domesticity.

When the couple moved to Botany in 1886 so that Andrews could work as a wool-washer, they took in boarders to make ends meet. Rumours circulated in the tight Botany community that Louisa enjoyed drinking with the men who stayed in their home.

In early 1887 Andrews took ill and after a few days of excruciating pain he died. Louisa's behaviour immediately after his death was viewed unfavourably by police and local gossips, especially as she did not don mourning clothes and applied for access to Andrews life insurance. Within two months of being widowed, Louisa married Michael Collins, a former boarder, pregnant with his child.

Collins was not good with money and the insurance funds dissipated quickly. Their infant son John died, and Louisa's older children were not fond of their new stepfather. In mid-1888 Collins took ill, with symptoms similar to Andrews, and died on 8 July. Almost immediately Louisa was arrested for his murder by poisoning.

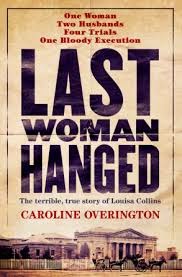

What happened next was appalling. Louisa Collins was tried - four times - by a prosecution determined to convict. The evidence against her was entirely circumstantial and there was much to suggest that both men may have became poisoned through their work as wool washers as skins were treated with arsenic. She had an extremely ineffective defence attorney and her young daughter May was compelled to give evidence against her. The first three trials resulted a hung jury, but the last, with a backdrop of media frenzy, voted to convict. These four trials occurred in rapid succession with gross misconduct on the part of many of the judges.

What happened next was appalling. Louisa Collins was tried - four times - by a prosecution determined to convict. The evidence against her was entirely circumstantial and there was much to suggest that both men may have became poisoned through their work as wool washers as skins were treated with arsenic. She had an extremely ineffective defence attorney and her young daughter May was compelled to give evidence against her. The first three trials resulted a hung jury, but the last, with a backdrop of media frenzy, voted to convict. These four trials occurred in rapid succession with gross misconduct on the part of many of the judges.Overington combs through the evidence for and against Louisa and highlights many inconsistencies which lead the first three juries to be unconvinced of her guilt beyond reasonable doubt. She also explored the historical context of the rise of the women's suffrage campaign, the temperance movement and the sensationalism of the media. What emerges is a travesty of justice in which a woman was killed by the State in a most horrific way.

This book was intriguing in many respects with Overington's skills as a journalist lending weight to her research. I particularly enjoyed the story of the early feminism in Australia. I learned a great deal about how autopsies were performed in hotels, the travel by tram around Sydney, and about the medical fraternity of the time. Although I need no further evidence to support my stance against capital punishment, this book was a reminder of how State-sanctioned killing is immoral and unjust.

I did not particularly like Overington's writing style, however, and felt that some of her turns of phrase distanced me from the content. She included many asides where she presented information with a modern gaze, and would have been better off sticking purely to the facts. An example is when she was talking about Alexander Green, one of the first hangmen in NSW. Overington writes "like most normal people, Green did not set out to become a hangman...". This sentence jarred me as judgemental and unnecessary. Later she writes about Louisa's fate moving to Parliament house "... in about the time it took to traverse the distance by foot. Well, not quite, but the point is made." The point could have been made without the poor analogy. This occurred regularly throughout the book and I wished it had been better edited prior to publication to remove some of these clunky asides.

But overall I am pleased that I read the book and had a glimpse of this time in our history. This book is recommended to those with an interest in history or the judicial system.